Eva Roubíčková (1921 - 2013)

She was born as Eva Mändlová into the family of a respected teacher at a Žatec grammar school. In a predominantly German-speaking town of Žatec the Mändl family was no exception, distinguishing itself perhaps only with its Jewish religion.

Eva spent a happy childhood, even though the 1930s brought more and more anti-Semitic attacks, as the majority population came under greater sway of the prevailing racist and nationalist ideology. The situation escalated in 1938 (prior to the Munich Agreement) – insults and slanders from classmates and teachers at the grammar school, persecution and beatings in the streets, stones thrown into their windows – that was the reality of everyday life in Žatec. That was also why the Mändls had opted for the desperate step and moved to Prague where they lived in various lodgings for three years before being put on a transport to Terezín (Eva with her mother on December 17, 1941, transport Nos. N 68 and N 69, her father due to illness later, on August 10, 1942, transport No. Ba 596).

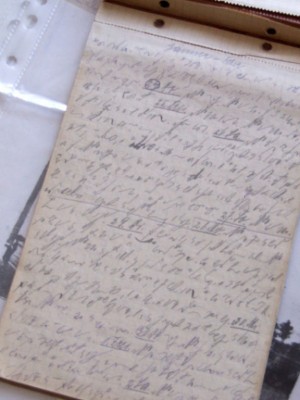

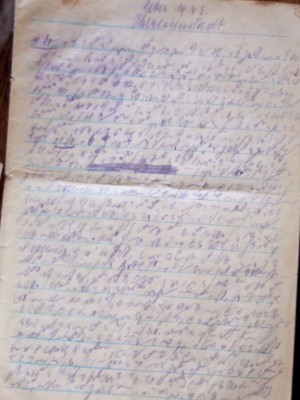

In January 1941 Eva began to write her diary, recording at first the miserable life of Jews in Prague, their own deportation and later nearly three and a half years spent in the Terezín Ghetto.

The diary offers a unique insight into the situation in the Ghetto, describing not only the destitution of its inmates and their fear of the transports to the “East”, as the deportations to the extermination camps were vaguely described. It also gives many details from the “routine” life in the Ghetto, including its widespread “favoritism” and “graft” among the inmates themselves.

At the beginning, Eva was lucky to get a job in the Ghetto’s farming sector. With her colleagues she grew vegetables and raised farm animals. Eva also used to feed the dogs kept by the local SS officers. All this helped her to live a relatively “better life“ than other inmates in the Ghetto. She smuggled vegetables from the Ghetto fields in such quantities that she managed to keep the living conditions of her entire family (mother, father and members of the extended family numbering another 5 people) at a tolerable level. Furthermore, something quite incredible happened to her soon after she stared her farming job, something that eventually brought her advantages as well as fear and threat to her life. One day she was accosted by an “Aryan” (as she initially called him) in a field outside the Ghetto who came from the nearby town of Bohušovice nad Ohří. From then on, Karel Košvanec, that was the man’s name, supplied Eva (and other inmates) with large amounts of food as well as cigarettes, newspapers etc.

In her diary Eva describes on many occasions her gratitude to Karel Košvanec, in other entries she says she would be happier if Karel stopped his help for good. In fact, he jeopardized not only his own life and those of all his family members but, quite understandably, also the lives of all the Jews whom he had contacted. After all, contacts with “Aryans” from the camp’s vicinity were most strictly punished.

In October 1942 Eva was really caught by a busybody Czech gendarme; she was interrogated and spent several days in prison – she was sure she would be deported to the East. To her surprise she stayed on, while one of her closest friends she had inadvertently named during her interrogation as the supplier of some of the smuggled food had to go in the transport. Afterwards she could not live down the psychic shock and guilty feelings. There were other traumatic experiences that gradually marked the two years of her life in the Ghetto: constant fear of transports which occasionally carried away a friend, an acquaintance or a relative, everyday stress caused by scrambling for food, clothes, shoes etc., occasional moving from one building to another, fear of the SS officers, fear that her group meeting Košvanec would be disclosed etc.

A final blow to her psyche was the last wave of transports (known as the liquidation one) which gradually carried away Eva´s whole family. She then volunteered for a transport but paradoxically was not included... she stayed on in Terezín until its liberation. The last six months of her stay in Terezín, as described in her diary, is thus a stream of brief and general descriptions of the life in the Ghetto. The diary ends with an entry for May 5, 1945 with a laconic outcry: “Schluss, END!”.

This “end” was followed by a period of gloom and darkness for Eva. She came back to Prague and soon realized that the catastrophic reports brought back by Holocaust survivors from the East were true – her whole family had been murdered, she was all-alone. Alone with her remorse – why was it that she herself had to survive?...

Eventually somebody did return home – her fiancé Richard Roubíček who fled to Britain on the eve of the war (Eva was supposed to have come over too but since she had not been of age at that time Britain did not issue a work permit for her). Richard spent the war in Britain as a soldier of the Czechoslovak Army Abroad.

The two young people married in September 1945, and a daughter was soon born to them, followed by a son.

Karel Košvanec died in 1950 at the age of 49, probably as a result of his bravery in smuggling food to the Ghetto.

The Roubíček family had to endure adversity and injustices in communist Czechoslovakia too, since both parents were Jewish and of “non-working class” origin. What was worse, Richard was a member of the non-communist anti-Nazi resistance abroad… Yet both lived to see the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and enjoyed the years of freedom afterwards.

Richard died in 1993, Eva in 2013.

The diary of Eva Roubíčková was translated into Czech in the mid-1960s by Mr. and Mrs. Roubíček themselves. Officially the diary was published as late as in 1998, namely in English in the United States, to be followed by a German edition (2007) and then a Czech version (2009).

This is the only extant diary written by a surviving inmate that covers virtually the whole time of the Ghetto’s existence (from its early days to its liberation).