Egon Redlich (1916 – 1944)

During the 1930s Egon Redlich, then a 20-year old inhabitant of the city of Olomouc, was getting ready to make his dream come true – he wanted to leave Czechoslovakia and set up a new home in Palestine. He perceived his own “Jewishness” not as a religion but rather as ethnicity. However, similar “Zionist“ opinions were in the minority among the Czechoslovak citizens of Jewish descent (most of them wanted to merge into the local milieu, “to assimilate”). In spite of that the Zionist movement had its influence throughout Europe in the first half of the 20th century, while some of the distinguished personalities (e.g. Albert Einstein) endorsed its policies, and thousands of young people from Czechoslovakia headed to Palestine. Zionism proved to be all the more topical and significant during the 1930s after the rise of Nazism in Germany.

Gonda (as his friends used to call him) was active in the Zionist movement, he joined the physical training union Maccabi Hatzair – he excelled in table tennis and skiing, but most of all he wrote articles, gave lectures and organized cultural evenings etc. He loved art, music and especially literature. During the dark period following the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia he had to leave his law studies at the Charles University, but he carried on his activities and turned out to be one of the leading lights of the Zionist organization Hechalutz (he sat on its cultural commission) and he also led the Prague school for the immigration of Jewish youth. At the very last moment, in the fall of 1939, he managed to organize, together with a Danish charity organization, an operation aimed at saving 80 Czechoslovak children. Thanks to that they survived the war abroad.

He arrived in the Terezín Ghetto from Prague on December 4, 1941 in a special transport codenamed “Stab”, together with other leading Jewish personalities who then held important posts in the Ghetto’s Jewish Self-administration. Egon himself was appointed Head of the Department for Children and Youth, which set itself an uneasy task of creating tolerable living conditions in the camp for the thousands of children ranging from newborn babies to adolescents.

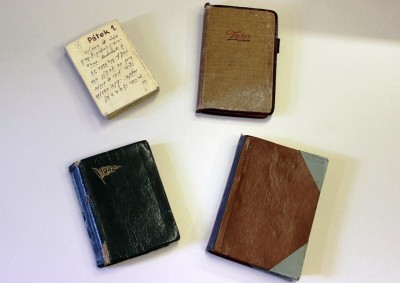

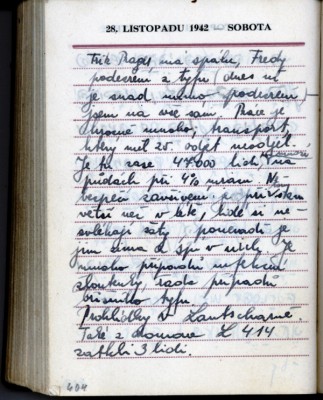

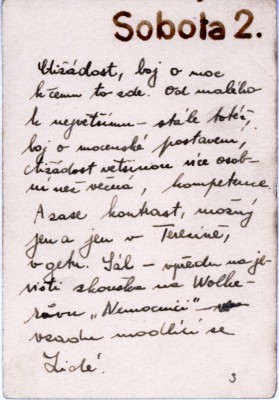

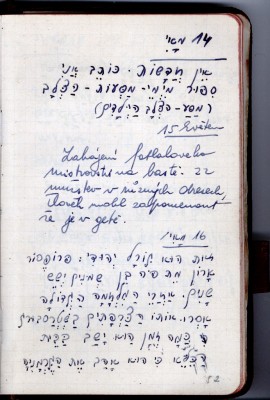

On January 1, 1942 he began to write a diary, committing to paper all his worries and observations. He wrote it in Hebrew (still hoping to find a new life in Israel after the war), while all Saturday entries were in Czech. The diary is a unique record presenting a colorful mosaic of life, as Egon came to know it in the Ghetto. It is also a sinister mosaic, with rays of hope penetrating only here and there. Egon describes the everyday reality in the Ghetto: deserted old people without family wandering about among the Ghetto’s tall houses, children – orphans living alone in the Ghetto, prisons, beatings of the inmates, executions, arrivals of devastated people, spread of diseases, death as a routine occurrence etc. But first and foremost, his diary contains evidence of the hardship and anguish the entire Ghetto population suffered whenever a new transport to the East was announced. According to the orders of the SS Camp Command the Jewish Self-administration had to draw up a list of names of the prisoners for that particular transport. Egon felt an enormous weight of responsibility for this horrible task and primarily for “reclaiming” (taking people out of the transport), which his commission was empowered to do. Could Egon ask for reclaiming children? Or their teachers and educators? But somebody else would have to be put in their places…

A large portion of entries in his diary reflect this particular dilemma Egon had to face in his post of Head of the Department for Children and Youth: how to take care of the thousands of children of different ages? Where to put them? Together? Or separate older from younger kids? What about the psychic problems experienced by children whose parents had left in transports or died in the Ghetto and who daily grapple with pangs of fear and anxiety? How to cope with the thefts of children? And so on and so forth. As time went by, a truly well-functioning body was built by Egon and his closest colleagues (especially Fredy Hirsch and Fritz Prager), an agency that succeeded in accomplishing what had seemed to be an impossible task: not only to provide the children in material terms but also – and primarily – to help them preserve their human dignity. Starting in the summer of 1942, children were concentrated in special homes, so called children’s homes (“kinderheim”). The Ghetto survivors recollect the unique atmosphere prevailing in the homes full of friendship, shared fun, zeal to create but also compassion and gratitude – in the world of the Ghetto these were oases of genuine childhood for the little inmates.

Egon Redlich (as many others) got married in the Ghetto; in September 1942 he married Gertruda Baecková with whom he had lived in Prague before deportation to Terezín. In March 1944 Gertrude gave birth to their son Dan Petr. The young parents encompassed their child with ardent love and Egon began to write a diary only for his son. He hoped they would manage to survive the agony of the war that seemed to be drawing to its end. Unfortunately they did not. The family fell victim of the last wave of transports from Terezín to Auschwitz, having left on October 23, 1944…

Egon´s diary was discovered in 1967 during a loft conversion in one of the terraced houses in Terezín. The English translation was published in 2015 under the title “The Terezin Diary of Gonda Redlich”.